#gede lwa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

More Pics From Fet Gede.

#fet gede#vodou ceremony#lwa spirits#gede spirits#spiritualism#voodoo altar#like and/or reblog!#follow my blog#african diasporic#african spirituality#new orleans voodoo#voodoo ceremony

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you tell me about Riley, Martine, and Charli’s families? Have you drawn any pictures of their parents or siblings?

I don't have any parent or sibling pics, sorry!

Riley is The New Kid, so if you've played the games, you know what her family is like. I keep waffling on her last name!

Martine's mother Marianne was a black woman, originally from South Carolina. Her mother killed herself, for yet-to-be-discovered reasons. Her father Daniel is French (white). Martine practices hoodoo to feel close to her mom, but she's a descenent of Gede Nibo, a powerful lwa/loa. She inherits his title as The Patron Saint of People Who Die From Unnatural Causes. It's her birth right. Daniel checked out after her mother died and is usually off on gambling trips. He's gone so much that when Martine is alone, Kenny can guess where he is.

Charli's tougher. They don't talk about her family much in the script. What we do know is her mom and Sheila were friends. Charli's mom (Jewish) is dead, and her dad (Haitian) looks like Rege-Jean Page and seems over protective. Charli's fear of sleeping, and the fact she doesn't seem to feel safe without Kyle (even though they fight like cats and dogs) hints that something traumatic happened to her but I could be reading between the lines too much.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baron Samedi (English: Baron Saturday), also written Baron Samdi, Bawon Samedi or Bawon Sanmdi, is one of the lwa of Haitian Vodou. He is a lwa of the dead, along with Baron's numerous other incarnations Baron Cimetière, Baron La Croix and Baron Criminel.

He is the head of the Gede family of lwa; his brothers are Azagon Lacroix and Baron Piquant and he is the husband of Maman Brigitte. Together, they are the guardians of the past, of history, and of heritage

Baron Samedi is usually depicted with a top hat, black tail coat, dark glasses, and cotton plugs in the nostrils, as if to resemble a corpse dressed and prepared for burial in the Haitian style. He is frequently depicted as a skeleton (but sometimes as a black man that merely has his face painted as a skull), and speaks in a nasal voice. The former President-for-Life of Haiti, François Duvalier, known as Papa Doc, modeled his cult of personality on Baron Samedi; he was often seen speaking in a deep nasal tone and wearing dark glasses.

He is noted for disruption, obscenity, debauchery, and having a particular fondness for tobacco and rum. Additionally, he is the lwa of resurrection, and in the latter capacity he is often called upon for healing by those near or approaching death, as it is only the Baron that can accept an individual into the realm of the dead.

Due to affiliation with François Duvalier, Baron Samedi is linked to secret societies in the Haitian government and includes them in his domain.

Baron Samedi spends most of his time in the invisible realm of vodou spirits. He is notorious for his outrageous behavior, swearing continuously and making filthy jokes to the other spirits. He is married to another powerful spirit known as Maman Brigitte, but often chases after mortal women. He loves smoking and drinking and is rarely seen without a cigar in his mouth or a glass of rum in his bony fingers. Baron Samedi can usually be found at the crossroads between the worlds of death and the living. When someone dies, he digs their grave and greets their soul after they have been buried, leading them to the underworld.

Baron Samedi is the leader of the Gede, lwa with particular links to magic, ancestor worship and death. These lesser spirits are dressed like The Baron and are as rude and crude but not nearly as charming as their master. They help carry the dead to the underworld

As well as being the master of the dead, Baron Samedi is also a giver of life. He can cure mortals of any disease or wound, so long as he thinks it is worthwhile. His powers are especially great when it comes to Vodou curses and black magic. Even if somebody has been afflicted by a hex that brings them to the verge of death, they will not die if The Baron refuses to dig their grave. So long as The Baron keeps them out of the ground, they are safe.

In many Haitian cemeteries, the longest standing grave of male is designated as the grave of Baron Samedi. A cross (the kwa Bawon, meaning "Baron's cross") is placed at a crossroads in the cemetery to represent the point where the mortal and spiritual world cross. Often, a black top hat is placed on top of this cross.

He also ensures that all corpses rot in the ground to stop any soul from being brought back as a zombie. What he demands in return depends on his mood. Sometimes he is content with his followers wearing black, white or purple clothes or using sacred objects; he may simply ask for a small gift of cigars, rum, black coffee, grilled peanuts, or bread. But sometimes The Baron requires a Vodou ceremony to help him cross over into this world

#baron samedi#lwa#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#afrakans#african culture#afrakan spirituality#haiti

178 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I found out recently that Baron La Croix owns my head but I can't find much about him online. Is there anything you know about him?

Hello!

Unless you passed through some kind of ceremony done by a houngan or manbo, you did not find out that a particular lwa owns your head. That information can only be determined when you are taking part in specific rituals within Haitian Vodou. It can't be determined by spiritualists outside the religion, via a casual reading, or anything else.

Moreover, all of the Barons are aspects of death and putting death on someone's head as their head spirit is inviting them to enter death quickly. We don't do that; the Bawons and various Gede are not put on heads or named as the met tet because we don't want people to die before God determines it is time.

Evdn further, the ceremonies that assign a master of the head are ceremonies of life where death can have no place; none of the Barons or Gede are allowed to have a presence so they certainly wouldn't be placed to the head.

I am happy to discuss the specifics of how this was communicated to you privately, if you'd like. Feel free to send me a message.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

RE: Was Baron Samedi worshiped in New Orleans prior to the late 20th century?

This one is also about the actual lwa.

Baron Samedi can aptly be described as not just the most iconic lwa, but one of the most iconic things from New Orleans Voodoo. Ironically, I have only found inconclusive evidence that he was worshiped in New Orleans during the 19th or early 20th centuries.

In American popular media, Baron Samedi is frequently conflated with other Haitian deities, called the Gede. The real-life Baron Samedi has his origins in Haitian Vodou, as does Maman Brigitte (Gran Brijit). The Haitian lwa are derived from African deities, among the most important being the Dahomean trickster god Legba (himself, derived from the Yoruba deity Eshu). Over the course of Haitian history, Dahomean Legba was refracted into Papa Legba, Met Kalfou, and the Gede - by extension, the Bawons, including Baron Samedi. This explains why the Gede are trickster deities of sexuality and liminality, who embrace all that is taboo - just like Dahomean Legba!

19th Century New Orleans Voodoo was greatly influenced by Haitian Vodou, due to the massive influx of Haitian refugees that arrived in the Crescent City after the Haitian Revolution. Following the post-Revolution migration wave, several Haitian lwa became features of New Orleans Voodoo, including:

Papa Legba → “Papa Limba” or “La Bas”, syncretized with St. Peter

Damballah → “Daniel Blanc”, syncretized with St. Michael

Agassu → “Yon Sue”, syncretized with St. Anthony

Ogou Feray could have also been worshiped as “Joe Ferraille” (“Joe Feray”), and Ayizan Velekete as “Vériquité”. While the Erzulies were not directly worshiped per se, veneration of Mother Mary was a key feature of 19th century New Orleans Voodoo. (The Erzulies are syncretized with Mother Mary.)

(I should also note that, in New Orleans, the lwa were called “spirits”, while Bon Dieu/Bondye was simply called “God”)

During the 19th century, the two most important lwa were probably Papa Legba - the Doorkeeper - and Damballah - the most ancient of the lwa. This would explain why their names appear most frequently in 19th- and 20th-century sources, especially in large scale rituals. Damballah might have been refracted into multiple deities, including “Daniel Blanc” and “Zombi the Snake God” – a deity famously associated with Marie Laveau. Others argue that “Grand Zombi” is actually derived from the Kongo supreme deity Nzambi Mpungu, or an invention fabricated by journalists.

A third key deity – “Onzancaire” / “Monsieur Assonquer” – might have been associated with Ogou Feray – one of the most important Haitian lwa. However, the origins of “Onzancaire” are elusive. Because so many different theories have been proposed, I do not know where his true origins lie.

Other deities of non-Haitian origin were also features of New Orleans Voodoo. St. Marron (Jean St. Malo) was the New Orleanian folk saint of runaway slaves. Mother Leafy Anderson – founder of the Spiritual Church Movement in New Orleans – introduced worship of the Native American Saint Black Hawk (see: Kodi A. Roberts (2015) Voodoo and Power: The Politics of Religion in New Orleans, 1881–1940). My understanding is that “Dr. John” (Jean Montaigne) was also deified, in a similar manner to St. Black Hawk. Orisha, such as Shango and Oya, may too have been worshiped. Other deities are listed here and here.

Baron Samedi is conspicuously absent. I think this has to do with the history of Haitian Vodou. Prior to the Haitian Revolution, Haitian Vodou was less of an organized religion, described as a "widely-scattered series of local cults" (see: The Social History of Haitian Vodou, p. 134). It was between the years 1804 and 1860 that Haitian Vodou began to stabilize into a clear predecessor of its present form. (see: The Social History of Haitian Vodou, p. 139) This period of stabilization took place after the migration wave of the early 19th century, which could explain why key features of Haitian Vodou are missing from 19th century New Orleans. For example, I have yet to find evidence that division of the Petwo and Rada lwa made it over to American soil. The refraction of Dahomean Legba might have never been transmitted by Haitian refugees, which would explain the absence of Met Kalfou and the Gede/Bawons from worship.

This too explains why the Papa Legba of American history was both Doorkeeper AND Guardian of the Crossroads. It has been theorized that the legendary “Devil at the Crossroads” was actually Met Kalfou. However, this “Devil” does not match the appearance of Kalfou, described as "no ancient, feeble man...huge and straight and vigorous, a man in the prime of his life." Instead, the one at “the Crossroads” appears as a limping old man who loves music and dogs (“Hellhound on my Trail”). It’s Papa Legba!

Rather than Kalfou, I think American Papa Legba actually inherits his more menacing attributes from Eshu. This would explain why he walks with a limp (like Eshu), is notoriously vengeful (like Eshu), and is sometimes described as androgynous (like Eshu!).

In any case, the Papa Legba of American history can be clearly traced back to Haiti. His appearance as a limping old man is inherited from Haitian Papa Legba; his love of dogs and music from Dahomean Legba. 19th century sources clearly identify him with Saint Peter (“St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door;”) The same cannot be said for Baron Samedi. He was probably not syncretized with St. Expedite, because St. Expedite “did not achieve popularity until the late 1800s or early 1900s in New Orleans” – long after the Haitian migration wave.

I have found one compelling source that places worship of Baron Samedi in 19th century New Orleans. Creole author Denise Alvarado is something of an expert on this topic, her being born and raised in New Orleans. In Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans (2022), Denise Alvarado identifies a “Spirit of Death” with Baron Samedi / Papa Gede. The most convincing piece of evidence comes from the second interview, in which the interviewee describes a ceremony where attendees donned purple robes. The color purple has been historically associated with Papa Gede (by extension, Baron Samedi).

That being said, I do think the evidence Alvarado provides is tenuous. Without additional context, it’s difficult to say whether the purple robes are truly linked to the Haitian lwa. The other newspaper article sounds rather sensationalized. The 19th century saw horrendous news coverage of New Orleans Voodoo, where reporters would exaggerate or straight-up fabricate details to demonize Vodouisants. The reporter’s description of the spirits of death does not align with the Haitian Gede or Bawons. It is important to remember that New Orleans Voodoo is not entirely Haitian in origin. Several other traditional African spiritualities are woven into New Orleans Voodoo. Prior to the Haitian migration wave of the early 19th century, one of the main influences was Kongo spirituality, in which ancestor veneration is central. Additionally, the newspaper cited is from the year 1890 – years after Marie Laveau’s death. The reliability of this article is therefore questionable. I think this could be a Damballah / “Grand Zombi” situation, where this “Spirit of Death” bears superficial resemblance to the lwa but isn’t actually him. It is also possible that he is simply a fabrication by journalists.

The defamation of Vodou continued into the early 20th century, as Haiti was occupied by the U.S. between the years 1915 and 1934. I don’t see how worship of the Gede/Bawons could have been transmitted to New Orleans between the end of the Haitian migration wave and year 1934. There’s a good chance that Baron Samedi / Papa Gede only properly became features of New Orleans Vodou during the revitalization movement of the late 20th century.

As such, I propose two hypotheses:

Baron Samedi was not properly worshiped in New Orleans until the late 20th century. He quickly rose in popularity, as he was easily grafted onto the pre-existing worship of the spirits of the dead (ancestors).

Alvarado has correctly identified Baron Samedi / Papa Gede with the “Spirit of Death”; however, this “Spirit of Death” was a radical departure from his Haitian predecessor, taking on a markedly different form from the lwa.

But that’s all just a Theory… A GAME THEORY!!!

…Anyways, annotated bib:

Marshall, Emily Zobel. American Trickster: Trauma, Tradition and Brer Rabbit. Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

Chapter 1 ("African Trickster in the Americas") describes Dahomean Legba’s origins in the Yoruba deity Eshu.

Cosentino, Donald. "Who is that fellow in the many-colored cap? Transformations of Eshu in old and new world mythologies." Journal of American Folklore (1987): 261-275. https://www.jstor.org/stable/540323.

From the abstract: “Myths of Eshu Elegba, the trickster deity of the Yoruba of Nigeria, have been borrowed by the Fon of Dahomey and later transported to Haiti, where they were personified by the Vodoun in the loa Papa Legba. In turn, this loa was refracted into the corollary figures of Carrefour and Ghede.” Accessed here: https://www.centroafrobogota.com/attachments/article/24/17106647-Ellegua-Eshu-New-World-Old-World.pdf

Haitian immigration : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. The African American Migration Experience. https://www.inmotionaame.org/print.cfm@migration=5.htm

Describes post-Haitian Revolution migration wave like so: “the number of immigrants [from Haiti to New Orleans] skyrocketed between May 1809 and June 1810… The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free persons of African descent, and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its population.”

Fandrich, Ina J. “Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 37, no. 5, 2007, pp. 775–91. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034365. Accessed 23 June 2024.

Mentions worship of Ogou Feray as “Joe Ferraille”. Fandirch herself cites Long, C. M. (2001). Spiritual merchants. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, p. 56: https://archive.org/details/spiritualmerchan0000long/page/56/mode/2up?

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 247: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT247#v=onepage&q&f=false

Mentions worship of Ayizan Velekete as (the male) “Vériquité”.

Anderson, Jeffrey E. Hoodoo, voodoo, and conjure: A handbook. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2008, p. 15: https://books.google.com/books?id=TH7DEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15#v=onepage&q&f=false

Relevant quote: "Blanc Dani, Papa Lébat, and Assonquer make the most frequent appearances in both nineteenth- and twentieth-century sources. The first two, in particular, figure prominently in large-scale rituals."

Humpálová, Denisa. "Voodoo in Louisiana." (2012). https://dspace5.zcu.cz/bitstream/11025/5338/1/BP%20Denisa%20Humpalova%202012.pdf

One of several sources that identifies “Grand Zombi” with Nzambi Mpungu.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 247: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT247#v=onepage&q&f=false

Posits that “Grand Zombi” could be derived from Nzambi Mpungu, or "may be the invention of journalists inspired by "zombie tales" of Haiti's infamous living dead, combined with Moreau de Saint-Méry’s endlessly repeated description of a snake-worshiping ceremony in colonial Saint Domingue."

Anderson, Jeffrey E. Voodoo: An African American Religion. LSU Press, 2024, p. 46: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Voodoo/O-v3EAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22assonquer%22+%22azewe%22+vodou&pg=PA46&printsec=frontcover

Describes several possible origins for the elusive “Onzancaire”, including a theory that he was a deity related to Ogou Feray.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 236: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT236#v=onepage&q&f=false

One of several sources to describe St. Marron (Jean St. Malo).

Roberts, Kodi A. Voodoo and Power: The Politics of Religion in New Orleans, 1881-1940. LSU Press, 2015, p. 82: https://books.google.com/books?id=EWOkCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT82&lpg=PT82

Describes how Mother Leafy Anderson (founder of the Spiritual Church Movement) “found” St. Black Hawk, introducing him to New Orleans Voodoo.

Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022, p. 39: https://books.google.com/books?id=ktlWEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39#v=onepage&q&f=false

Posits that high priestess Betsy Toledano worshiped the Orisha Shango and Oya during the 19th century.

Anderson, Jeffrey E. Hoodoo, voodoo, and conjure: A handbook. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2008, p. 15: https://books.google.com/books?id=TH7DEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15#v=onepage&q&f=false

List of deities worshiped in 19th century New Orleans Voodoo.

Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022, p. 126: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Witch_Queens_Voodoo_Spirits_and_Hoodoo_S/ktlWEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA126

Another list of deities worshiped in 19th century New Orleans Voodoo.

Mintz, Sidney & Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (1995) “The social history of Haitian Vodou” in Cosentino, Donald J., ed., Sacred Arts of Vodou, Chapter 4. LA: UCLA Fowler Museum, 123-47. P. 134: https://ghettobiennale.org/files/Trouillot_Mintz_LOW.pdf

Describes Haitian Vodou as a "widely-scattered series of local cults" prior to the Haitian Revolution.

Mintz, Sidney & Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (1995) “The social history of Haitian Vodou” in Cosentino, Donald J., ed., Sacred Arts of Vodou, Chapter 4. LA: UCLA Fowler Museum, 123-47. P. 139: https://ghettobiennale.org/files/Trouillot_Mintz_LOW.pdf

Describes the stabilization of Haitian Vodou into a predecessor of its current form. This occurred between the years following the Haitian Revolution and year 1860.

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen : The Living Gods of Haiti. New Paltz, NY: McPherson, 1983 (originally published in 1953), p. 101: https://archive.org/details/divinehorsemenli00dere/page/100/mode/2up

Description of Kalfou (Carrefour) as "no ancient, feeble man...huge and straight and vigorous, a man in the prime of his life." Deren conducted her ethnographic work during the 1940s and 1950s.

Marvin, Thomas F. “Children of Legba: Musicians at the Crossroads in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.” American Literature, vol. 68, no. 3, 1996, pp. 587–608. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2928245. Accessed 23 June 2024.

Description of “The Devil at the Crossroads” as a musical genius and “limping old black man”: “Most versions of this story instruct the aspiring musician to bring his instrument to a lonely crossroads at midnight and await the arrival of a limping old black man who will tune the instrument, play it briefly, and then return it endowed with supernatural power."

Robert Johnson’s song “Hellhound on My Trail” identifies “The Devil at the Crossroads” with Papa Legba, who is associated with dogs.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 244: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT244&lpg=PT244#v=onepage&q&f=false

Relevant quote: "Mary Washington, born in 1863, said she was trained in the arts of Voudou by Marie Laveau. She remembered a song that was sung at the weekly ceremonies: "St. Peter, St. Peter open the door; I am callin' you, come to me; St. Peter, St. Peter open the door." Mrs. Washington explained that "St. Peter was called La Bas, St. Michael was Daniel Blanc, and Yon Sue was St. Anthony." She also mentioned a spirit called Onzancaire."

Alvarado, Denise. The Magic of Marie Laveau: Embracing the Spiritual Legacy of the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2020, p. 57: https://books.google.com/books?id=SZOMDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA57&lpg=PA57#v=onepage&q&f=false

Relevant quote: “Baron Samedi remains a popular and powerful force in New Orleans Voudou today, along with his wife Manman Brigit. He is syncretized with St. Expedite, among the most popular of saints in New Orleans. We do not hear of St. Expedite in association with Marie Laveau, however, because he did not achieve popularity until the late 1800s or early 1900s in New Orleans (Alvarado 2014).”

Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022, pp. 127-128: https://books.google.com/books?id=GsofEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA127&lpg=PA127#v=onepage&q&f=false

This is the strongest evidence I could find that Baron Samedi / Papa Gede was worshiped in 19th - early 20th Century New Orleans.

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen : The Living Gods of Haiti. New Paltz, NY: McPherson, 1983 (originally published in 1953), p. 107: https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.505921/page/107/mode/2up?q=purple

Historical evidence that, since at least the 1940s, Papa Gede’s colors are “black or purple”. To this day, purple is associated with Baron Samedi and the Gede as a whole.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 250: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT250&lpg=PT250

Relevant quote: “The religion that evolved in nineteenth-century New Orleans and was embraced by Marie Laveau and her Voudou society combined traditions introduced by the first Senegambian, Fon, Yoruba, and Kongo slaves with Haitian Vodou, European magic, and folk Catholicism. It also absorbed the beliefs of blacks imported from Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas during the slave trade of the 1830s–1850s. These “American Negroes” were English-speaking, at least nominally Protestant, and practiced a heavily Kongo-influenced kind of hoodoo, conjure, or rootwork. New Orleans Voudou is therefore not identical to Haitian Vodou, but represents a unique North American blend of African and European religious and magical Traditions.”

Fandrich, Ina J. “Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 37, no. 5, 2007, pp. 775–91. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034365. Accessed 23 June 2024.

Describes major Senegambian and Kongo influences on New Orleans Voodoo, prior to the Haitian Revolution. Relevant quote: “New Orleans's African population was Kongo dominated with a strong affinity with the spirits of the dead…Dahomeyan influence occurred only indirectly through the Haitian refugees who "flooded" the city after 1808. In 1809 alone, more than 10,000 Haitians arrived, and doubled the city's population. They brought their Vodou religion with them, which ultimately merged with the already existing New Orleans or Louisiana Voodoo traditions. During the French colonial regime, 80% of the enslaved Africans came from one single ethnic group: the Bamana (also called Bambara) people from the Senegal River basin (today's Senegal, Gambia, and Mali), most of them stemming from one single ethnic group, the Bambara people. The majority of the remaining 20% were Kongolese and some Dahomeyans (Hall, 1992). Despite their rather different geographical origins, these two cultures blend easily into one another. Eighteenth-century Louisiana Voodoo maintained a marked Senegambian flavor, with some Kongolese elements blended in, until the end of the 18th century.”

Dubois, Laurent. “Vodou and History.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 43, no. 1, 2001, pp. 92–100. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2696623. Accessed 23 June 2024.

An overview of the history of Haitian Vodou, as it pertains to U.S. history. Demonization of Vodou continued past the U.S. occupation of Haiti, until the late 20th century.

#between the two it is 100% papa legba who had a bigger impact on horror stories from the american south of the early 20th century#i think a lot of people would think it's baron samedi but no! it's the mischevious limping old man!#commentary#the loa (hazbin hotel)#baron samedi (hazbin hotel)#big papa legba

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ah, yes. November 2nd.

Feast day of the the Gede. Bawon Samndi.

He would be busy with cooking, preparing some hearty, homely meals, a good batch of beignets, assorted snacks, and, naturally, a healthy assortment of various rums.

He could most likely be found in the gardens, the veve of his patron drawn on the ground with white sand, the feast neatly set up around it.

Later in the evening, he would light a bonfire, meticulously built to fit the occasion.

He was honoring his Lwa. His patron. And the entirety of the Gede clan.

He would be busy for the rest of the night. It was a feast, after all.

It could get rowdy.

#alastors-radioshow#drabble#//If anyone needs him.... He's gonna be a tad busy today. He takes this very seriously.#//Just a little notion uwu

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martine was made for South Park so... She'd be home lol.

Let Kenny can have his cute voodoo lwa psychopomp girlfriend, you know? He deserves people to hang out with who can travel between life & death and who remember he died!!

And since she's descended from Gede Nibo (Patron of People Who Died From Unnatural Causes!!!) Kenny always has a direct line to her and Nibo no matter what condition he's in.

also look how cute they are??? anyway I love them <333

Quick! The first OC you think of is dropped in the world of the last movie/show you watched. How are they faring?

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghostly Fairies Master List Part 3:

Ghostly fairies are associated with death and may not have a set physical appearance; some appear as orbs of lights.

Abúhuwa

Adya Houn'tò

Ahalgana

Ahalpuh

Aïapakal

Akeki

Amatsénka

Aña (Bolivian mythology)

Anamaqkiu

Animal Masters (Innu)

Aroe (Borôro)

Arun (Orisha)

Arutam (Shuar)

Atshen

Atwuskniges

Ayizan

Babalú-Aye (Orisha)

Bah tha (Stoney Nakoda)

Balichù

Baron Criminel

Baron Cimetière

Baron La Croix

Baron Samedi

Biri (Orisha)

Bonhomme Sept Heures

Bope (Borôro)

Bukùbulu (Matambú)

Caboclos (Candomblé)

Cauchemar

Cemís/ zemís (Taino)

Cuchumaquic/ Cuchumaquiq

Diyin Dine'e

Dry Fingers/ Oniate/ O’nya:ten

Ela (Orisha)

Elegua (Orisha)

Elel (Puelche)

El Bracamonte

El Gritón

Flying Head (Haudenosaunee and Wyandot)

Gahe (Apache)

GA'ntu yê'gî (Fire Spirit)- https://www.sacred-texts.com/nam/nw/tmt/tmt103.htm

Gede (Haitian Vodou)

Gualichu

Haghwehdaetgah

Hekura (Yanomamo)

Hobomock (Chepi)

Hoklonote

Ho-no-che-no-keh

Huaca (Quechua)

Huitranalhue

Icheiri/ Chemin (Carib)

Iku (Orisha)

Ikxareyavs (Karok)

Itqiirpak

Jaguar (Yanomami)

Jai (Emberá)

Kachpikh

Kanaima

Kalfu (Maître Carrefour, Mait' Carrefour, Mèt Kalfou, Kafou) (loa)

Kilyikhama

Kimpungulu/ Mpungu

Kobayende

Kokou (orisha)

Kosmenk (Selk'nam)

Kotaix (Selk'nam)

Kuntiniu Nukuri

Lagua (Haida)

La Tunda

Leba (Winti)

Lemba (loa)

L'inglesou (loa)

Lox (Wabanaki)

Lusifee (Wabanaki)

Lwa/ Loa/ Loi

Mademoiselle Charlotte (loa)

Mãe do Ouro (compare to Malachite Maid)

Mafia spirits (Garifuna mythology)

Maîtresse Délai (loa)

Maîtresse Hounon'gon(loa)

Ma Kengue (Palo religion)

Mama Aisa

Maman Brigitte(loa)

Maninkari

Manitou

Manze Marie (loa)

Marassa(loa)

Marinette(loa)

Maroule(loa)

Mastop Kachina

Matshishkapeu

Medicine Man Kachina

Mesingw

Metres Ezili

Mohan (South American)

Mombu(loa)

Kugin Jaad/ Mouse Woman

Muut

Nagual

Na���In

Nalusa Falaya/ Impa Shilup

Nana Buluku (Orisha)

Narnauk

Nekedzaltara

Ngen (Mapuche)

Ngen-kura (Mapuche)

Ngen-mawida (Mapuche)

Ngen-wingkul/ winkul (Mapuche)

Nukatem

Nsasi (Palo religion)

Orisha

Orò (Orisha)

Oualapatou

Papa Gede

Papa Legba (loa)

Patan (Mayan)- https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/religion-and-philosophy/lords-xibalba-mayan-myth#:~:text=The%20Lords%20of%20Xibalba%20are,challenges%20designed%20to%20test%20visitors.

Petro lwa

Pihuicheñ/ Peuchen

Pillan (Mapuche)

Quezubû

Rada lwa

Raven Mocker/ Kâ'lanû Ahkyeli'skï

Saci (Brazil)

Shakpana

Shiwanna (Pueblo)

Silap Inua

Slender Man

Soorts (Selk'nam)

Sousson-Pannan

Tahquitz

Tanu (Selk'nam)

Tariaksuq

Tatankan Gnaskiyan (Lakota)

Tau (Guarani)

The Master of Night (Menominee)

The Moongazer

The Wind-Man (Maidu)

Ti Kita (loa)

Ti Malice(loa)

Tinihowi

Tuurngait (Inuit)

Úgai

Wakanpi

Wakan Tanka

Wangulén (Mapuche)

Winti- https://sacredart.caaar.duke.edu/religions/surinamese-and-dutch-winti/

Wuya (Hopi)

Ya’i spirits of the mountains- https://huuayaht.org/about/history/

Xic (Mayan)

Xiquiripat

Yashigo (Candoshi)

Yei

Yewá (Orisha)

Yoshi (Amahuaca)

Yua

Yutuyuturi- https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers17-09/010004394.pdf

Zemi

0 notes

Text

How To Make Peppered Vodka For The Gede Spirits.

Learn one of the the offerings that is giving to the Gede Spirits. This simple drink recipe is on my Community Page.

#Gede offering#vodou loa#vodou lwa#like and/or reblog!#google search#follow my blog#ask me anything#vodou offering#gede spirits#new orleans voodoo

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

HEY APRIL I LOVE YOUR WRITING! I know you have OCs but which ones are your favorite? (yours or someone elses)

omg thank you, I love this question!! 💚🧡💙💔

The credits are included in each write up, but this post includes OCs, artwork, scripts, fics and audio from me, @short-story-unhappy-ending, @angel-gone-dark, @kats-spblog, @musturdslt, @used-to-love-her-06, @fennecfiree and of course @south--of--nowhere

💖Charli Lafayette

Origin: South Park Bridgerton script, @short-story-unhappy-ending (comic adaptation) Artwork by: @short-story-unhappy-ending, @kats-spblog, @angel-gone-dark and @south--of--nowhere Audio by: @musturdslt Charli is such cutie! She's Haitian and Jewish! She has Queef Sisters PJs! I love all the romance tropes and romcom references in the script, which makes sense because it's a Bridgerton satire, but omg! The fake relationship!! The arguing!! the sleep-cute!! Shoving those tropes into a South Park script and keeping it authentically SP sounds impossible but it works.

Charli and Kyle have great chemistry because she has a really distinct personality, that makes her a really a fun foil for him. Another weird thing I like is that Charli Lafayette and Kyle Broflovski have the same amount of syllables in their names??

So much thought went into her character and it shows! I think that's why she's the most popular character on this list. There's even an audio clip of what Charli would sound like speaking Creole on the show and it's SO CUTE.

💖Riley

Origin: My New Kid!!!! Artwork from: FBW, Piccrew Riley was my very first South Park OC!! I love her so much, she is everything!! She's the moment! She has selective mutism, which can really complicate her life. Writing a fic with a character that doesn't speak but still communicates was challenging, but fun.

Riley is loyal to a fault. She will always go out of her way to help others - even to her own detriment. She's quite intelligent, but also incredibly naive. She's Ethiopian and Jewish.

Riley and Kyle will often meet up at the synagogue on Saturdays and talk shit about Cartman. She bonded with Kenny over having shitty parents. Sometimes they'll both sneak out of the house and patrol in their supersonas together.

Her superhero name is Joystick - because she breaks all the games they play (SOT, FBW, Snow Day) by being way too OP. 💔

💖 Martine Guede

Origin: Warm Blood (18+ content) by ME! Artwork by: me, @angel-gone-dark Martine is an average girl... She speaks French and plays piano. She got dumped by Kyle. She's a villain working for Professor Chaos. She practices Voodoo and Hoodoo! She is a psychopomp, Descended from Gede Nibo -- a Lwa, and the Patron of People Who Die From Unnatural Causes. Which means she can remember Kenny's deaths because she is a member of the Gede/Guede. I love the villain/hero romance between her and Mysterion. Kenny and Martine falling for each other and doing the enemies to lovers trope (While she thinks he's unaware of her secret identity!!) is EVERYTHING to me. I love them so much. She's half black and half French (I was inspired by Charli, let me LIVE) and her relationships with Kenny and Kyle such a tangled little web. The flashback chapter when Kyle and Stan meet Martine is one of my favorite things.

💖Leigh

Origin: He's Got His Mother's Hips (18+) by @angel-gone-dark Artwork by: @angel-gone-dark Leigh is just your average trans boy trying to survive in South Park... Oh, and he's a pretty powerful villain. He might be dating Professor Chaos. And might have a thing with Mysterion. Oh! By the way, did I happen to mention that he's besties with a girl named April? What a coincidence! 😉 Honestly, Leigh is super compelling as a protagonist and he's a fucking OP villain. I wonder what would happened if he faced off against Riley!? South Park probably wouldn't survive lol.

💖Aviv

Origin: @used-to-love-her-06 Artwork by: Piccrew Aviv is the only OC on this that's not from the South Park fandom! She's a Slipknot girlie. Aviv's story spans 27 years! Which is honestly so fucking cool! Like I'm not jealous someone came up with that idea before me. I am totally not inspired to make PC-aged OC or anything... Aviv is Jewish and a fucking rock star... How could I not love her?

💖Tiffany

Origin: South Park (Unnamed BG Character) Artwork by: @south--of--nowhere, @angel-gone-dark & @fennecfiree Tiffany is a background character that me and my friends kind of adopted. She's a total cutie and I love her design so much!! She was named after the Fall Out Boy song Tiffany Blews.

#south park fanfiction#south park#south park fanfic#sp fanfiction#south park original character#south park oc#south park au#south park comic#sp comic#sp fan art#south park fan art#south park fan fiction#south park fan comic#south park fandom#south park fanart#kyle broflovski#kenny mccormick#sp kyle#sp kenny

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Remi took a swallow of juice, nodding.

“Oh yes! Each one has special days, colors, scents, plants, animals, foods and drinks they all enjoy.”

He nibbled at a strawberry, and sat one aside. There was the laughter again, and in a whisper of red smoke, the berry vanished. Dantour loved her sweets, and strawberries were a favorite.

“ You can make offerings on your own, like I just did, and they’re not too likely to respond to non-practitioners, or you can bring an offering to someone in the religion…hougan or mambo, a sort of high priest or priestess, and they can make the offering for you, and ask the Lwa to help you, or simply be more favorable to you. “

He sat another berry aside, further from him, and though it vanished too, nothing marked its disappearance this time.

“Even though the Lwa that chose Alastor is different than mine, I still make offerings to him as well as my own. It’s always best manners to honor all the Lwa in a house, even if they’re not yours, because it’s very rude. It’s Like, lavishing attention on one houseguest, and ignoring the other.”

He loved to talk about what he could of his religion. Though most of his mortal youth was part of a cannibalistic hunting cult, based loosely on Alastor…and actual voodoo.

Thankfully he and Sebastian, his biological sibling, were raised by the cult’s resident mambo. Remi had been blessed with the gift more than Sebastian, and that was fine. Bastian had the brains and brawn, Remi had the power.

Too bad in the end Remi had lost his mind in a terrible accident, and by then Sebastian became too debauched and jaded to keep things going. A few too many mistakes, and the cult was destroyed, the boys with it.

“Did you have any particular Lwa in mind you wanted to offer to? The only other Lwa I know that are left is Bawon, that’s Bawon Samdei, lord of the gede Lwa, the kings of the cemetery and the dead. His wife is Madame Brigette, and it’s he who guards the house in the swamp where I live with Alastor. He’s the one who chose Alastor, like how Miss Dantour chose me.”

"Remi? I know the practice of voodoo is a very closed off religious practice but.. if it alright to say would you tell me about the Lwa?"

Remi smiled.

“I can tell you plenty of things, just can’t teach you the magic or rituals, but I can tell you what I know of the Lwa I work with and have met if that helps?”

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A death rite in Haitian Vodou

Here is a rare look at the publicly viewable portion of desounay/desounen, which is the first rite after a houngan, manbo, or other vodouizan passes. Unfortunately, this was a rite done on behalf of the death of a very well known and well respected houngan in Jacmel, Haiti who died unexpectedly this morning. This is difficult to watch, with lots of crying and expressions of grief.

youtube

The video begins with the procession, which has likely started at the home of the houngan (Woodson Antoine, ki di Gwètòde Plenipontansyè), where he passed, and is leading into the temple where Houngan Sonson was initiated. The procession ends as the rest of the desounay is completed behind closed doors. After, folks who have arrived gather to hear Houngan Woodson's papa kanzo speak, and then the videographer shares the news that Houngan Woodson has passed and shares what details were available; that he has been in ceremony just hours earlier with many of the people present, had not been well and had many health issues, had been encouraged to go to the hospital, and then went home, where he passed due to breathing difficulties. By the time an ambulance was found, he had already gone. The videographer compares desounay to the Catholic rite of extreme unction, which is aimed at allowing someone sick to pass to eternity with the blessings of their God and forgiven of their sins. Desounay is a little different than that, as it is only completed after death.

The desounay is completed as soon as possible after death is realized; this is the first ceremony that begins to separate our various soul pieces to go where they must so that we, our lwa, and our descendants can have peace after we pass. It is preferable that this ceremony is done before the body is taken from the home to the morgue or funeral home. In this case, you can see how quickly it was put together; it is happening very early in the morning, pre-9AM, and folks have clearly come directly from ceremony or their homes in a rush, you can see that they have put their white clothes on over other clothes or black and purple clothes from the Gede ceremonies they were attending. This has happened so quickly that there has not been time to prepare the temple or really even the community; Houngan Woodson was extremely well known in Jacmel and in Haiti at large due to his position as gwètò and not everyone was able to come in the moment to share in the grief. His bowoum and traditional internment will undoubtedly be huge.

This is a huge loss. While Haitian Vodou professes no central authority figure(s), a gwètò is a sort of regional coordinator that takes on the responsibility of watching over the community/communities in his or her region. A gwètò might mediate disputes, help a new temple start up, and represent the region throughout the country. Houngan Woodson took his position seriously and attended just about every ceremony in the area, even if he could only go for awhile. I personally benefitted from his intercession when there were local issues my husband needed help with, and I knew Houngan Woodson to be a kind, thoughtful, and caring individual who was always pleased to see me and hear how I was.

This has been a very introspective Gede season for me; Gede has had me sitting and reflecting on things that I will write about soon. What I have thought about today in thinking about this particular death is that access to healthcare is a liberation issue. While only Bondye knows our time and we ask to only be taken at our right time, had Haiti had more equitable access to both emergency medical care in that someone could have called for help and Houngan Woodson could have gone to a hospital that was staffed and had medical equipment, and regular healthcare that could have provided ongoing support for his medical issues as we know in many other parts of the world, perhaps his death could have been avoided. If liberation was fully realized in Haiti, deaths from things we take for granted as minor annoyances, like asthma, strep throat, high blood sugar, and similar, would be a thing of the past.

Woukoukou, yon gwo pyebwa te tonbe. May Houngan Woodson awaken in the company of his ancestors and his lwa in Alada, and may his friends, family, and loved ones find comfort in his memory.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Scrapped Concept) Maman la Vie

This is the last time I’m planning to draw this character, and her male counterpart, as they were both conceived in poor taste.

Lengthy explanation / rant below cut:

WHY THIS WAS A TERRIBLE CONCEPT FROM THE START

Long ago, I grossly mischaracterized the real-life Baron Samedi and Maman Brigitte like so:

…In the actual mythology Baron Samedi is like a womanizer who is cheating Maman Brigitte all the time. Maman Brigitte is also really promiscuous…

…In Voodoo, Maman Brigitte is portrayed as a white or light-skinned biracial woman because Maman Brigitte is the only one of the Loa that is European in origin, not African…

OOF! I CRINGE!!!

In all seriousness, the above is an incredibly offensive mischaracterization of the lwa.

Let’s start with Baron Samedi: I confused him with a different category of spirits, called “Gede”. The male Gede are known for being overtly sexual, but it is not because they are adulterous lechers. They celebrate sexuality because sexuality is the process by which life is created, for death is entwined with life. They also do this for the purpose of mocking social hierarchy - namely, the race/caste system that emerged out of chattel slavery. Zora Neale Hurston describes this at length in Tell My Horse. The reason why the Gede wear top hats actually pertains to this. The Gede are often portrayed as dark-skinned, for they are the spirits of enslaved people. Hence, the favorite spirit of the Black peasantry adopts the dress of the white slave-owning class - the top hat - for the purpose of mocking this social hierarchy. Their overt sexuality also serves this purpose - to alienate the white upper class.

My description of Maman Brigitte is yet more egregious. She is not promiscuous at all, nor is she Caucasian, biracial, or light-skinned.

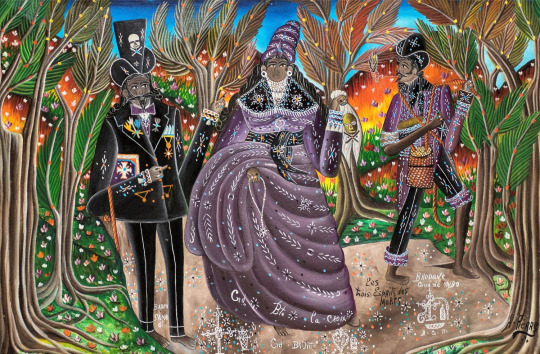

Here is how the lwa are portrayed by the master painter, Andre Pierre:

Pierre portrays the lwa with a range of skin tones, where some of the lwa (e.g., Ezili Freda, Damballa Wedo) are portrayed as lighter skinned. Maman Brigitte is shown next to Baron Samedi in the bottom right corner.

Here is closer shot of Maman Brigitte, alongside Baron Samedi and Gede Nibo:

Maman Brigitte is portrayed as dark skinned, with the same skin tone as Baron Samedi and Gede Nibo. Additionally, she is not promiscuous, but a dignified and reserved older woman.

Andre Pierre is not the only Haitian artist to portray her in this manner. She is consistently portrayed this way by Haitian artists, such as Gerard Paul:

And Roudy Azor:

Eziaku Atuama Nwokocha describes Maman Brigitte (Gran Brijit) like so: “Gede, like all lwa, has many incarnations, including Bawon Samedi, a guardian of the cemetery; Gran Brijit, an old woman, keeper of the cemetery, and Gede’s partner; and Gede Nimbo, a male spirit who is often honored by queer people and who appears as an effeminate dandy.” (p. 37)

Elsewhere: “Gede’s delighted embrace of sexuality is an undeniable display of male desires. The spirit manifests in multiple genders, like his female counterpart Gran Brijit, but only the male version are so explicitly sexual. No female deity in the Vodou pantheon expresses sexual desires so emphatically or bluntly in a ceremony. There are female spirits who are coy, mysterious, vengeful, or wise, but not one proudly proclaims her sexual desires…” (p. 39-40)

Much like her male counterparts, there is a lot of nuance to the portrayal of Maman Brigitte’s sexuality (rather, lack thereof). This too pertains to the history of slavery and the manner in which racism is gendered: “During the centuries of enslavement in Hispaniola, enslaved Black women were subject to routine sexual abuse from White enslavers and others with the power to dominate them. To justify this commonplace brutality, Black women were constructed as hypersexual temptresses and prostitutes who were always available for sexual conquest...To combat the construction of Black women as hypersexual, their sexual desires were ignored entirely, characterized by reductive binaries that placed whores on one side and good, chaste Christian women on the other: there was no room for the actual desires of real women."

Source: Nwokocha, Eziaku Atuama. Vodou en vogue: fashioning Black divinities in Haiti and the United States. UNC Press Books, 2023.

Hence, my description of the lwa was incredibly offensive. I read it from a source that turned out to be not reputable. I apologize for being so careless in my research.

I do not know why the portrayal of Maman Brigitte as a White or Half White woman has persisted in the public consciousness. Surely, it is because it reinforces racist stereotypes of Black men and colorism against dark skinned Black women. But I think it is also because her name sounds so similar to the Celtic Saint. This does not mean that she is White. For example, the name “Baron Samedi” sounds European. If you didn’t know any better, you might think he is French, as “Samedi” is a French word. But the “Samedi” in “Baron Samedi” is distinctly non-European in origin. It is either derived from the indigenous term Zemi, or it is African in origin. Similar statements can be said to the lwa that arrived in New Orleans; Damballah became “Dani Blanc”, Ogou Feray became “Joe Feraille”, etc. Vodouisants were forced to Europeanize the names of these ancestral deities, who can trace their origins back to Africa. I remain uneducated about the true origins of Maman Brigitte, and it is something I have been meaning to research.

A while back, I spoke to a guy from Haiti on this topic. He got really ticked off and started talking about how terrible portrayals of Baron Samedi and Gran Brijit are. One of the main things he emphasized was how they play into fucked up, racist stereotypes of Black people. He got so pissed off I never got a chance to get to the root of the matter. Now that I’ve taken the time to research this more carefully, I realize just how horrendous the mischaracterizations are. Incredibly offensive descriptions are written in books, which turn into characters in various media that perpetuate these stereotypes. Just look at how common it is to see Baron Samedi portrayed as a lecher, and Maman Brigitte portrayed as a Caucasian or biracial woman! I didn’t fully grasp the gravity of what this man was trying to impress on me, until now. I completely underestimated the volume of misinformation that exists, and the appalling degree to which Vodou has been disrespected.

I really cannot stress this enough: The lwa are comparable to Catholic Saints. They are not these Satanic demons, and have only been mischaracterized as such due to the demonization of African religions that is rooted in the history of slavery. As far as I can tell, Baron Samedi really is one of the most misrepresented of the lwa; so is Maman Brigitte. Should they ever be put into Hazbin Hotel, I think it would be best to pay tribute to the great Haitian painters of the 20th century. To do otherwise is deeply disrespectful to people in New Orleans, Haiti, and other places in the diaspora. But perhaps this whole endeavor illustrates why it is a mistake to put either one of them into the show - that it does cross the line into cultural appropriation.

My depiction of the “Maman Brigitte”-type character and her male counterpart for sure crosses the line of cultural appropriation... It’s. SO. BAD!!!! I for sure deserve to get canceled for this one… Hence, I intend to correct this egregious error.

I might not have communicated this well in my previous post, but this is my intention: I have no plans to proceed with the old concept of “Maman la Vie” or “The Baron of Death”. This is the last time I plan to draw either one of them. I want to proceed with what I have been calling “the alternate concept” (i.e., “Baron of the Dead” and “Gran Maman”). I want to swap this “alternate concept” in, and move the old concept into a scrapped folder. If I had the time, I would for sure just go back, redraw old drawings, and delete the old concept. Unfortunately, I work full time, so I probably do not have time to do this. But the old concept bothers me so much, if I have time I will go back and fully redo this. In the meantime, my plans are to develop and proceed with the “alternate concept” (i.e., “Baron of the Dead” and “Gran Maman”). At minimum, I want to draw both of them at least once and refine their character descriptions. These would be moved into the main folder, replacing the old concept.

I hope that makes sense… it probably doesn’t…. Sorry, my brain is tired and communication is not my forte…my creative process is a hot mess and the inner machinations of my mind are an enigma…

ACTUAL IMAGE DESCRIPTION

I still drew her one last time because she is very fun to draw. I would be lying if I said I did not love this character on some level… Her personality is so outrageous, it is really funny to me. This tiny, under 5’ woman is the craziest sexual sadist in all of existence…!

In my brain, this makes so much sense. If you’re the immortal goddess of life who can heal any injury… your mind probably would go to that place, wouldn’t it…?

But yeah. This was totally conceived in poor taste…just, just start firing nukes at me!!! However, I love this character too much to completely scrap her, so instead I am going to reinvent her as a demon. A character with this personality clearly belongs in the setting of Hell. It’s so easy to just turn her into a demon, I don’t know why I didn’t think of this from the start.

That demon character is named “Lavi”. I guess these outfits would be outfits she might try on if she were to ever assume a human disguise… But she would probably only wear them briefly before stepping into a discount Harley D. Quinn fit.

The dress on the left is inspired by Nina Kristofferson as Billie Holiday. The dress on the right is inspired by a dress worn by Josephine Baker on May 5th 1953, when she appeared as Flower Girl at the Famous Charity Ball of the "Little white Beds" held at the Moulin Rouge, Paris. At that, I totally think someone in the cast of Hazbin Hotel has got to be styled after Josephine D. Baker herself - ideally, Alastor’s mother. I like that idea so much, I’m actually tempted to try to draw my take on canon Alastor’s mother…

#hazbin hotel oc#maman la vie (hazbin hotel)#she really is the discount harley quinn to end all discount harley quinns…#i dont even care. i love harley quinn so much!#but yeah… i’m not going to proceed with this character.#this is also bad character design because i just completely plagiarized that one other guy’s (girl?s) portrayal of the lwa#and made it so much worse… that’s one of my favorite portrayal of baron samedi and maman brigitte ever#they just look so fucking cool#in all seriousness i really apologize for this... part of this is because i thought of big papa first and everyone else was an afterthought

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Now, this is, evidently, an older drawing. But little did I know, at the time of drawing this, that it was the beginning of the situation I’m now in.

You see, I am a vodouisant. Or voodooist, if you prefer. And this right here, is my patron Lwa. Baron Samedi. He’s more than just a patron to me, though. But that’s possibly something I might wanna talk about at a later point, since this is about the drawing. I decided to finally upload this, after having seen many posts about him, so I thought that I’d share this old piece.

In Voodoo, you don’t pick what Lwa you wish to work with. The Lwa picks you. I didn’t even pick Voodoo. I was kind of just thrown into it. So Voodoo picked me. And in turn, the Lwa I currently work with picked me. And how he picked me? Well, might post about that later. But gods be damned, he scared the shit out of me, and I had no idea what had just happened, haha.

Anyway. I just wanted to finally post this drawing, because I’m still awfully fond of it, though I’ve made many pieces featuring this guy since then. I’ve, naturally, evolved my drawing techniques since then.

To think that it took me 4 years to actually kick myself in the butt hard enough to upload it. I need to get better at just uploading my drawings and cosplays when I have them, in stead of procrastinating XD

#drawing#traditional drawing#traditional art#watercolor#water color#watercolor drawing#watercolor painting#baron samedi#bawon#bawon samedi#baron samndi#bawon samndi#voodoo#vodou#haitian vodou#new orleans voodoo#lwa#ghede#gede#gede lwa#ghede lwa#voodoo lwa#vodou lwa

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

The much taller entity rolled his eyes. This man clearly had some issues in regards to how to address people. Especially people with more authority than himself.

But that wasn't his issue to fix.

"Name's Bawon Samndi. The Lwa of the dead. Head of the Gede." He explained, simply. He was death. But it wasn't his name.

"He ain't dead, no. I don't know what happened, that's what I'm 'ere ta' find out." He'd murmur, crouching down next to the body.

"'Deathlike' is th' right word."

Death? That was who this man was? That was believable. The shadow demon stood up, wiping his eyes of tears once more. Even knowing the stag wasn't dead, Ombra couldn't bear to look at what greatly resembled his friend's dead body. It made him sick to his stomach.

"Well, Death, if he's not dead, then what's happened to him? He seems so... deathlike. Can he be saved?"

#nebula-gaster#alastors-radioshow#::On With The Show:: - RP#::M!A - Sleeping Death::#::Guest Muse - Bawon Samndi::

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultural backgrounds: Anansi

Anansi is a popular folktale character and cultural hero. He is from Ghana, originating from the tales of the Akan people. He quickly got a good place in the Ashanti mythology and his legends spread across all of West Africa, and then into the Caribbean folklore.

Sometimes called Kwaku Anansi, Kompa Nanzi or Nancy, Anansi is described as both a spider (Anansi meaning “spider” in the Akan language) and a humanoid being – his depictions ranging from fully human-looking or completely spider-like to hybrids such as a spider with human face and clothes or a man with eight limbs. He is often described as having a family: he has a wife, that bears different names according to the sources, and several sons (Ntikuma, his first-born son, Tikelenkelen, his big-headed son, Nankonhwea, his son with spindly necks and legs, and Afudohwedohwe, his big bellied son). Some story also tells of Anansewa, the beautiful daughter of Anansi that he tries to wed to the most profitable parties.

Anansi is a famous trickster, renowned for his ruses, his cunning, his talent at making speeches and his skills as an orator. The Akan consider him an Abosom (equivalent to the Yoruba orishas and Vodun loas). The Abosoms are in the Akan spirituality powerful spirits, akin to lesser gods, that helped shape the world and are a link between the mortal, earthly beings and the supreme entity that is Nyame, the Sky Father. Anansi is said to be either the son of Nyame and Asase Ya, the Earth Mother, or merely their servant and messengers. However, Anansi never received any intense worship and his divine nature was never put forward by the Akan, who felt that his role as a cultural figure and folklore hero was much more useful than his religious aspect.

Among the many legends about Anansi, two stick out the most because they each explain one of Anansi’s role in the world.

The first story explains that in the beginning the world was story-less, for all of them were kept in a box by Nyame, the Sky Father. Anansi thought the world was boring and thus went up at the top of the universe to meet with Nyame and ask from him the box of stories. Nyame, impressed that Anansi managed to reach him with his silk strings, agreed to give him the stories in exchange for the capture of extremely dangerous creatures, such as the Python, the Leopard and the Hornets. Anansi managed to capture all these deadly beings through ruses and tricks, and Nyame gave him the box. That is why today Anansi is considered the master of all stories in the world and the patron of storytellers.

The second story says that a long time ago, the clever Anansi craved for more intelligence,and set out on a quest to collect all of the knowledge in the world. Then he put all of this wisdom into a jar (or a calabash) and decided to keep it all for himself. Searching a safe place to hide his treasure, he chose to put it on top of a high tree. He tried several times to climb the tree while holding the jar, or tying it to his belly, to no use. Anansi hadn’t noticed that his son, Ntikuma, had secretly followed him, curious about what his father may be doing. When Ntikuma suddenly shouted at Anansi that to carry the pot all up to the tree, he had to carry it on his back, Anansi got a shock due to the surprise.

Here the story splits in two popular versions. In the first one, Anansi, surprised, let the jar out of his hand, and it crashed on the ground. Immediately, a storm came and its rain washed all of the world’s wisdom away in the river. Anansi, angry at his son, chased him under the rain until he realized that having all the world’s wisdom was not useful if you still needed the help of a child to do things right, and forgave Ntikuma. The other version rather has Anansi following his son’s advice, and climbing on the top of the tree with the jar, only to conclude the same thing as in the other version. He then threw the jar himself onto the ground, so that the wisdom would be free to spread in the world. This story explains why Anansi isn’t merely considered as a clever and cunning trickster, but also as a “wise” figure and the one who offered knowledge and wisdom to the world. (Some like to claim that the box of stories of Nyame and the jar of wisdom of Anansi are one and the same [1]).

But these are just two of Anansi’s many stories. Another one tells of how he created the first inanimate human body, another speaks of him as the one who brings rain in the mortal world and causes the floods. He is also considered the one who taught human how to plow and sow. A legend says he created the sun, the moon and the stars and thus was responsible for days and nights[2], and another explains that he helped Owia the Sun, youngest son of Nyame, to gain his father’s role as the chief of the world, against his two older brothers Esum the Night and Osrane the Moon, and that for his services Anansi became Nyame’s personal messenger. A last tale explains that when all of the animals in the world fought over who was the oldest, Anansi won the argument because he explained that, when his father died, he had to bury him in his own head, for the earth didn’t exist back then.

Fittingly for Anansi, master of storytelling, his survival and the spread of his popularity across the globe was due to him being part of an oral culture – unwritten traditions and stories that spread from mouth to ear in all of the western African continent before going over to the Caribbean Islands, and then the New World. Indeed, when slaves were brought over from the Caribbean and the African continent to the Americas, they told each other the stories of Anansi – the “anansesem” or “spider tales” in the Ashanti language, a specific genre of tales for children centered around the Spider adventures. Since most of these stories told of a little, weak spider turning the table on powerful oppressors through his cunning and his tricks, Anansi quickly became a symbol of resistance and survival during the slavery era – and telling his tales was a way for the slaves to keep their original identity and culture alive.

However, this transition from the Old World to the New World modified Anansi’s characterization. While in America he became a classical hero to admire, imitate and follow, originally Anansi wasn’t a paragon of moral virtues. He was a flawed character and while his stories often showed him as, indeed, the winner or the survivor of a world turned against him, sometimes Anansi brought unfortunate events upon himself or the world due to his own vices – the “anansesem” were entertaining and instructive, yes, but also a warning against how avarice and selfishness could be our own undoing.

For example, a story explains how Anansi, supposed to find Nyame a wife among a village of beautiful maidens, decided to take all of them as his own wives without any of them for Nyame, and when the Sky Father “stole back” all of Anansi’s wives for his personal harem, the Spider unleashed all of the sicknesses existing upon the world as a way to get his revenge. Another explains that Anansi one day received meat from Death itself to feed his family. However, upon seeing that Death had endless supplies of meat (for everything living in this world belongs to Death), Anansi became greedy and stole from Death. Death, angry, followed Anansi back to punish him and while the Spider evaded it, he still brought mortality into the world of the living. A last story explains how Anansi announced to all the animals that Gun, the personification of firearms, their deadly archenemy, was dead and invited them to his funeral. What the animals didn’t know was that in fact, Gun wasn’t dead, and Anansi had borrowed him from the Hunter – thus, once all the animals were reunited, Anansi killed them all and then took their bodies to his home so that he may feast on them.

Anansi was included into the Haitan Vodou as a Gede Lwa. The Lwa or Loa, falsely called “gods” of vodou, are powerful spirits forming an in-between stage between the mortal creatures and the supreme being, while the Gede were a specific family of Loa associated with death, the afterlife and funerals. As a Loa Gede, Anansi was supposed to establish or facilitate the link between the living and their deceased ancestors. [3]

#american gods#cultural backgrounds#mr. nancy#anansi#africa#mythology#legends#ghana#akan#west africa#carribean#kwaku anansi#kompa nanzi#abosom#ashanti#gede lwa#loa#vodou#old gods#cultural hero#folklore character

3 notes

·

View notes